[This is a bilingual note. Español más abajo.]

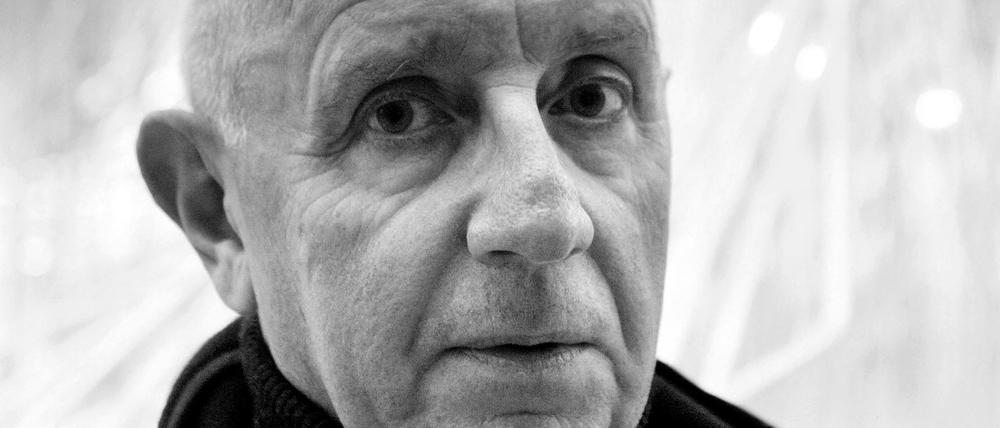

[EN] Last month, the French thinker Paul Virilio died. We knew about it on September 18th, and today, thanks to the obituaries, we know that the so-called Blitzkrieg Baby past away on the 10th day of that month (Wark, 2018; Bishop & Parikka, 2018). All the more, those homage-texts throw on our faces the urgencies that —while Virilio used his entire life to point them out— we, ignorants, many times prefer to avoid. That is why by doing a parenthesis to the path I have drawn for these notes, I want to sketch here, briefly, only two things —there many others— regarding what the French thinker’s legacy offers us.

I.

Virilio was initially trained in a school of applied arts. There, he specialized himself in the design of stained-glass windows. Times long past. I think that maybe in that way he looked, through a color-stained and striated translucency, the ruins left by the outbreak of an epoch —the Blitzkrieg—. Blast and vision that triggered, perhaps, the transit, his transit; the glass that cuts the gaze, connects the perception invariably —perhaps as in Barthold Heinrich Brockes (Kittler, 2010, p. 90-91)— to a dispositif which takes us towards the first stop that phenomenology constitutes. Thus, Virilio harbors himself in Merleau-Ponty’s seminars in Paris, for then, we are told, finding his first love in architecture (Wark, 2018).

The man who was presented as urbanist and philosopher for decades, was anything but that, and all that at the same time; because his object was velocity —that phenomenon with no halt brought by the war that does not stop, ever again—.

II.

In my own transit, I held not long ago an academic role in place whose devotion spun around the notion of dwelling. I looked at it with distance, many times with total skepticism. Because when Virilio’s early glass became a machine, this time stained by information, the territory dwelled insofar as social cartography, the city dwelled insofar as political complexity, the built environment which is dwelled as eternally modern typology, are simply not enough. Their lethargy does not allow to see the hyper-velocity pointed out by Virilio.

The questions lie in another time. The issue, beyond being descriptive, of finding itself on the surfaces, is now —or again— ontological.

Thus, the verb dwelling, undoubtedly problematic, requires still of a subject for being, so to speak, grammatically executed? Then, regarding the predicate, what is that that is dwelled? And all the more, insisting with some cynicism in the subject, who-what dwells? Thus, the object is not so indirect anymore —nor a mere object—.

Virilio’s velocity, the one through which he pointed out disappearance, invariably shows that we do not dwell only (in) one place, but many; moving, disappearing. Therefore, there is no place anymore, but only time. Because of that, we are not longer what we were, and dwelling will not be what once was, never again.

This ontological question does not relate, certainly, “only with things, their matter and form, but […] with relations between things in time and space” (Kittler, 2009, p. 24).

In times like these —running between things—, it is not possible to be stained-glass windows designer anymore. Neither urbanist or philosopher (Virilio, Kittler & Armitage, 1999).

***

[ES] El mes pasado murió el pensador francés Paul Virilio. Nos enteramos de su muerte un 18 de septiembre, y hoy, gracias a sendos obituarios, sabemos que el así llamado Blitzkrieg Baby, falleció el día 10 de ese mes (Wark, 2018; Bishop & Parikka, 2018). Más aún, esos textos-homenaje nos echan a la cara las urgencias que —mientras Virilio se ocupaba de señalarlas durante toda una vida— nosotros, muchas veces, ignorantes, preferimos pasar por alto. Es por ello que haciendo un paréntesis a la línea que he trazado para estas notas, quiero apuntar aquí, muy brevemente, sólo dos cosas —hay muchas más— sobre lo que nos señala el legado del francés.

I.

Virilio se formó primeramente en una escuela de artes aplicadas. Allí se especializó en diseño de vitrales. Tiempos ya lejanos. Pienso, tal vez, miró así, a través de una translucidez estriada bañada en color, las ruinas que dejaría el estallido de una época —la Blitzkrieg—. Explosión y visión que detona, probablemente, el tránsito, su tránsito; el cristal que se interpone a la mirada, conecta invariablemente la percepción —quizá como en Barthold Heinrich Brockes (Kittler, 2010, p. 90-91)—, a un dispositivo que lleva hasta la primera parada que constituye la fenomenología. Virilio, así, se cobija en los seminarios de Merleau-Ponty en París, para luego, nos dicen, encontrar su primer amor en la arquitectura (Wark, 2018).

El hombre que fue por décadas, usualmente, presentado como urbanista y filósofo, era nada de eso y todo eso a la vez; pues su objeto fue la velocidad —esa sin detención que trae la guerra que no acaba, ya jamás—.

II.

En mi propio tránsito, ocupé hace no mucho un rol académico en un lugar cuya devoción giraba en torno a la noción del habitar. La miré con distancia, muchas veces con total incredulidad. Cuando el cristal se convierte en máquina, esta vez bañada en información, el territorio que se habita en tanto que cartografía social, la ciudad que se habita en tanto que complejidad política, el espacio construido que se habita en tanto que tipología eternamente moderna, sencillamente ya no bastan. Su letargo, no permite ver la hiper-velocidad que apuntó Virilio.

Las preguntas yacen en otro tiempo. La cuestión, lejos de ser descriptiva, de hallarse en las superficies, es esta vez —o nuevamente— ontológica.

Así, aquel verbo, habitar, indudablemente problemático, ¿requiere aún de un sujeto que lo ejecute, gramaticalmente por así decirlo? Entonces, para el predicado, ¿qué es eso que se habita?, y más aún, insistiendo —con algo de cinismo— en el sujeto, ¿quién-qué habita? El complemento, ya no es tan indirecto —ni tan complemento—.

La velocidad de Virilio, aquella con la cual señaló la desaparición, muestra, indefectiblemente, que ya no habitamos (en) un solo lugar, sino múltiples; moviéndonos, desapareciendo. Por lo tanto, ya no hay lugar, sino, solo, tiempo. Por ello, no somos más lo que fuimos, y habitar, no será nunca más lo que alguna vez fue.

Esta cuestión ontológica, entonces, por cierto, no trata más “sólo con las cosas, su materia y su forma, [sino] con las relaciones entre las cosas, en el tiempo y el espacio” (Kittler, 2009, p. 24).

En los tiempos que corren —entre las cosas—, ya no se puede ser tan solo diseñador de vitrales. Tampoco urbanista o filósofo (Virilio, Kittler & Armitage, 1999).