[This is a bilingual note. Español más abajo.]

[EN] The notion of the archive has been particularly important for our countries —I think of you, oh, South-America!—. Fields in the humanities such as art history and visual studies, and somehow cultural studies too, have pointed out the central role of this notion when it comes to deal with the people’s historical and political memory.

However, I’m attempting to develop a different formulation here; perhaps an alternative one? And while I’m not totally sure of how to do it, because I don’t want to go just forward against what I have said in the previous paragraph, I seek, however, to point out to a different space and time —maybe earlier, perhaps ulterior—; there, where languages and systems of configuration lie, beyond what humans have said —even beyond what they think they have discerned and wrote by themselves (Foucault, 2010 [1969], p.181)—.

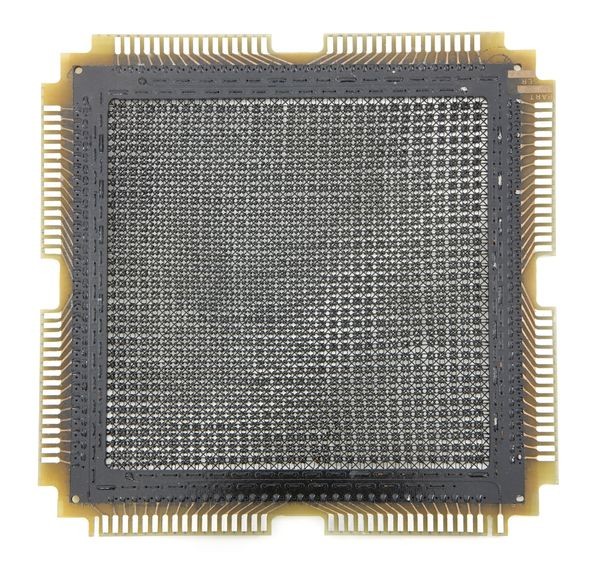

The archive, whose inner thread take us to the Greek word arché (ἀρχή), has been many times translated as origin —perhaps the myth of the Ark plays a role here?—. But even this oscillates between the perspective that approaches the archive as a place, and the other that insists into understanding it as a function of time —even the arks must travel and oscillate, once and again, through storms and noise—. Thus, if the archive were owned by time, then it would be process. As it has been suggested before: arché does not mean only origin, but principle too; principia and governing principle. Thus, from this perspective, ours, the archive is regulation and system of configuration: the archive is a machine.

Nonetheless, the archive begun to be erected as monuments for the muses; musealium —perhaps museum?— (Ernst, 2013, p.92). That is, as the place to safeguard the knowledge that humans had written and accumulated sheet of paper over sheet of paper; stacked, thus, with other sheets. Modernity however, gave course to a total discontinuity through the invention of universal machines —just as it’s said in a previous note—, whose mode of existence depended, alternatively, on paper being infinitely in movement; thus written, then erased, always in movement, again written, scanned, and erased once more —in movement, oscillating—.

The Universal Turing Machine —which didn’t take long to become universal in more than one sense— pushes us to deploy a meticulous reflection —where this note is only an invitation and not such act properly— on the archive, and on the scope of actualizing its inner condition to an extent which is thoroughly contemporary. This, because when monumental archives transit towards the regime of the digital —usually due to conservation needs—, their relation to the question of memory stops being mainly rhetorical or referring exclusively to the great temporalities pointed out by culture and its history (Foucault, 2010 [1969], p.17; Ibid., p.169), becoming, instead, dependent on micro-temporalities (Ernst, 2013, p.97).

Thus, when knowledge escapes from that cold waiting in the shelves —its wide latency—, moving continuously as flows of electrical charges deployed through telecommunication networks, then, its transformation is just radical: it is not knowledge anymore, but information; not latent, but transitory (Ernst, 2013, p.95). Then, the archive stops being only there, in the underlying laws of the texts protected by the mausoleums —as it occurred with no major perturbation until the 19th century—, becoming thus a permanent flux of information, and all the more, of data, that the very structure of the system which allow its existence, writes, erases and rewrites, once and again —transitoriness—. In times of high technology, the archives becomes precisely a function of such transitoriness —techné and logos—, and hence, the same occurs to the question of memory.

This implies that the archive can only exist under one condition: the memory in which it rests must always be technical —flip-flop—; and thus, too, always transitory (Ernst, 2013, p.96). Not far from that, the media theorist Friedrich Kittler anticipated, twenty-five years go, that the question of the memory should be analyzed with attention to its random character —Random Access Memory—, and that this applied to when it was approached from the beginning, the end, or from any middle point of the path that can be drawn between Freud’s psychoanalytic project, and the most advanced technological developments in Japan (Kittler, 2017 [1993], p.129-30). Then, Wolfgang Ernst’s “archives in transition” insist and emphasize the problem: the micro-temporalities through which technical memories advance, their hyper-velocity, unapprehensible to our senses, take us to perceive every transitoriness, every rewriting, every past, just and only as the present (Ernst, 2013, p.87).

In sum, when human existence is coupled, insofar as swarm, to this archive, what remains is the urgency to ask for, and thus rethink, the actual place of memory in these media-cultures of ours —and with that, to ask for its (perhaps) historical boundaries, as well as for its politics of circulation. In other words, we should ask what is the place we take in this technical feed-back, or well, what is the place that feed-back takes in our place.

***

[ES] La noción de archivo ha sido especialmente importante para nuestros territorios —te pienso ¡oh, Sudamérica!—; campos humanistas como la historia y teoría del arte, los estudios visuales, y también, por qué no, los estudios culturales, se han ocupado de señalar el lugar central de ésta en la cuestión de la memoria histórica y política de los pueblos.

Sin embargo, me preparo para avanzar en una operación distinta, ¿acaso alternativa? No sé bien como hacerlo. No quiero ir a contrapelo de lo antes dicho, pero al mismo tiempo, quiero apuntar a un espacio, a un tiempo, diferentes; tal vez anterior, quizá ulterior. Allá donde yacen los lenguajes y sus sistemas de configuración. Más allá de lo que los seres humanos han dicho, o incluso, han creído discernir y escribir, por ellos mismos (Foucault, 2010 [1969], p.181).

El archivo, cuyo lazo interior nos lleva hasta la voz griega arché (ἀρχή), ha sido muchas veces señalado como el principio, como el origen —¿el mito del arca? Pero, aquello oscila aun entre la aproximación que mira al archivo en tanto que lugar, y la otra, que insiste en entenderlo como función del tiempo —incluso las arcas deben viajar, oscilar, sí, otra vez, a través de las tempestades y el ruido. Y si él fuera del tiempo, entonces el archivo es proceso. Ha sido dicho antes: principio no es sólo origen, sino también principio gobernante, principia, principle. Así, desde esta perspectiva, la nuestra, el archivo es ordenamiento, sistema de configuración; el archivo es máquina.

Sin embargo, el archivo comenzó erigiéndose en tanto que monumento a las musas, musealium —¿acaso museo?— (Ernst, 2013, p.92). El lugar que resguarda el saber que los seres humanos han escrito, acumulado, papel tras papel, apilados, así, junto a otros papeles. La modernidad tardía empero, dio curso a la discontinuidad total que significó la invención de máquinas universales —tal como señala una nota anterior—, cuyo modo de existencia dependía de que, en cambio, el papel estuviera infinitamente en movimiento; así escrito, luego borrado, entonces, siempre en movimiento, nuevamente escrito, escaneado, y otra vez borrado —y así, otra vez, en movimiento, oscilando.

La Máquina Universal de Turing —que no tardó mucho en convertirse en universal en más de un sentido del término— obliga a desplegar entonces una reflexión minuciosa —donde esta nota es sólo la invitación y no el acto propiamente tal— sobre la noción de archivo y el alcance de actualizar su condición hasta un punto en detalle contemporáneo. Esto, pues cuando los archivos monumentales transitan —casi siempre por necesidad de conservación— hacia el regimen de lo digital, su relación con la cuestión de la memoria deja de ser principalmente retórica, o bien, de estar referida exclusivamente a las grandes temporalidades que señalan la cultura y su historia (Foucault, 2010 [1969], p.17; Ibid., p.169), pasando en cambio a obedecer a una condición de micro-temporalidades (Ernst, 2013, p.97).

Más aún, cuando el saber huye, por así decirlo, de aquella fría espera en los estantes —su holgada latencia— para avanzar y moverse ahora, sin parar, en tanto que flujos de cargas eléctricas desplegadas a través de redes de telecomunicación, entonces, su transformación es radical: ya no es saber sino información, ya no es latente sino transitorio (Ernst, 2013, p.95). Así, el archivo deja de estar puramente ahí, en las leyes subyacentes de los textos cobijados en esos mausoleos —como fue sin más hasta el siglo XIX—, pasando a ser un flujo permanente de información, y más aún, de datos, que la misma estructura del sistema que permite su nuevo modo de existencia, tal discontinuidad, le exige ser escrito y borrado, y nuevamente, escrito y borrado, una y otra vez —transitoriedad. En tiempos de alta tecno-logía, el archivo pasa a ser una función precisamente de aquello —techné y lógos—, y en consecuencia, lo mismo ocurre con la cuestión de la memoria.

Esto es, el nuevo archivo puede existir sólo a condición de que la memoria en la que descansa sea siempre técnica —flip-flop—, y así, también, siempre transitoria (Ernst, 2013, p.96). No muy lejos, el teórico de medios Friedrich Kittler adelantaba, hace veinticinco años, que la cuestión de la memoria debía analizarse precisamente con atención a su carácter aleatorio —Random Access Memory—, bien fuera ésta abordada en el inicio, el final, o cualquier punto medio del trayecto que se dibuja entre el proyecto psicoanalítico de Freud, y los más altos desarrollos tecnológicos del Japón (Kittler, 2017 [1993], p.129-30). Luego, los “archivos en transición” de Wolfgang Ernst, vienen entonces a insistir, y a acentuar, el problema: la micro-temporalidad en que avanzan las memorias técnicas, su hiper-velocidad, inaprensible a nuestros sentidos, nos lleva a percibir toda transitoriedad, toda re-escritura, todo pasado, sólo como presente (Ernst, 2013, p.87).

En suma, cuando la misma existencia humana es acoplada, como enjambre, a este archivo, lo que queda entonces es la urgencia de preguntar por, y así re-pensar, el lugar de la memoria en estas culturas-mediales —y con ello, por cierto, por sus límites (acaso) históricos, y, más aún, sobre sus políticas de circulación. Puesto de otro modo, nuestro lugar en el feed-back, o el feed-back en nuestro lugar.